Berlin - Gesundbrunnen

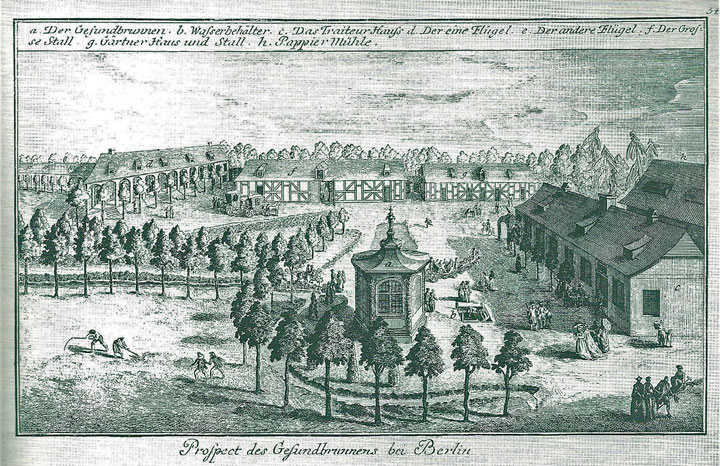

The first historical record on the mineral spring Gesundbrunnen appeared in 1748. Consisting of two German words gesund and brunnen, it literally means healthy spring.

In 1751, local pharmacist Wilhelm Behm commissioned a chemical analysis of the spring by chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf, which confirmed the efficacy of its high iron content.

Containing a much higher sodium and iron content than other spas, the spring attracted praise from Friedrich II and the construction of a well and health retreat began in 1758.

As a result of the royal approval, the spa was named Friedrichs-Gesundbrunnen.

Known to relieve chronic and rheumatic diseases and eye ailments, the spa attracted a significant number of visitors every year.

Following the death of Behm in 1780, however, the spa was put on the market.

In 1808, physician and pharmacist Christian Gottfried Flittner acquired a well that drew from the mineral spring, and built an English garden around it.

In 1809, the spa was renamed Luisenbad after Queen Luise of Prussia, who regined at the time.

This was followed by several changes of ownership but the hustle and bustle of its heyday never returned.

In 1874, businessman Ernst Gustav Otto Oscholinski purchased the area, renaming it Marienbad, and set up a complex, consisting of a restaurant, swimming pool, beer garden, ballroom and café.

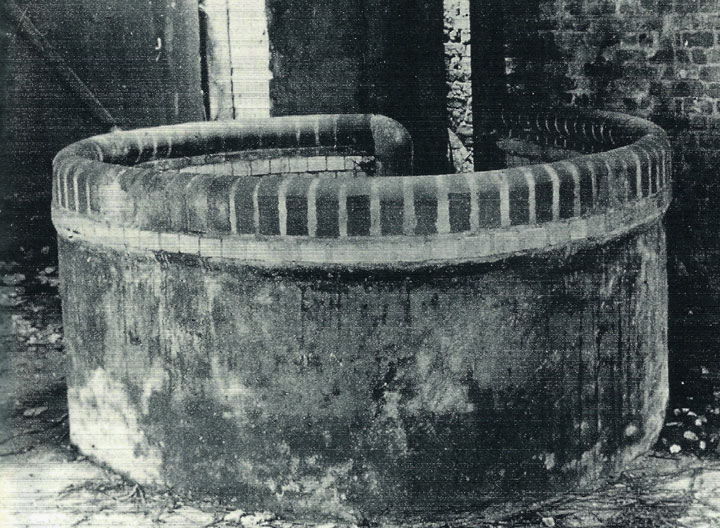

In 1876, master carpenter Carl Galuschki built his house over a well that also drew from the mineral spring and began bottling the water for distribution throughout Berlin and Germany.

In 1885, Galuschki acquired Marienbad. His brother Emil also built his new home in the area and opened a café and a dancehall designed in the Neoclassical style.

From this time onwards, the area around Badstraße became concentrated with beer gardens, bars, gambling houses and brothels.

Amid the city’s continued expansion, the construction of a sewer was underway in Badstraße. The accidental drilling into the well in 1891, however, caused irreversible damage to the spring.

The subsequent years saw the establishment of theatres, music cafés, and cinemas near Marienbad. However, in 1945, they were almost completely decimated from bombing by the Allied Forces.

Today, a relief that reads In fonte salus (Salvation is in the spring) sits at the top of the façade on 38/39 Badstraße.

Badstraße 38-39, Berlin

Berlin - Brunnenstraße 9

Leading to the site Gesundbrunnen, the building at Brunnenstraße 9, where the Times Art Center Berlin is located, was designed by architect Arno Brandlhuber and commenced construction in 2010.

The architecture and design offices are on the floor above the Art Center while the architect’s private residence sits two floors above. Until 2019, KOW Gallery occupied the site where the Times Art Center Berlin is a currently tenant.

An initial architectural project on this plot that was underway in the 1990’s came to an abrupt halt as a result of failed investments, at which point only the foundations and the underground structures were complete. Long abandoned, it became something akin to a ruin.

In 2006, Brandlhuber purchased this ruin after it had been on the market for 10 years.

Brandlhuber’s design cleverly incorporates what was already there, retaining the foundations and the underground structures while leaving the traces of the original construction visible.

The puddle of rusty red water and the steel reinforcement bars that appear as a key visual of the project are the photographic documentation reflecting previous states of the ruin.

Brunnenstraße 9, Berlin, Times Art Center Berlin

Berlin - Gartenplatz

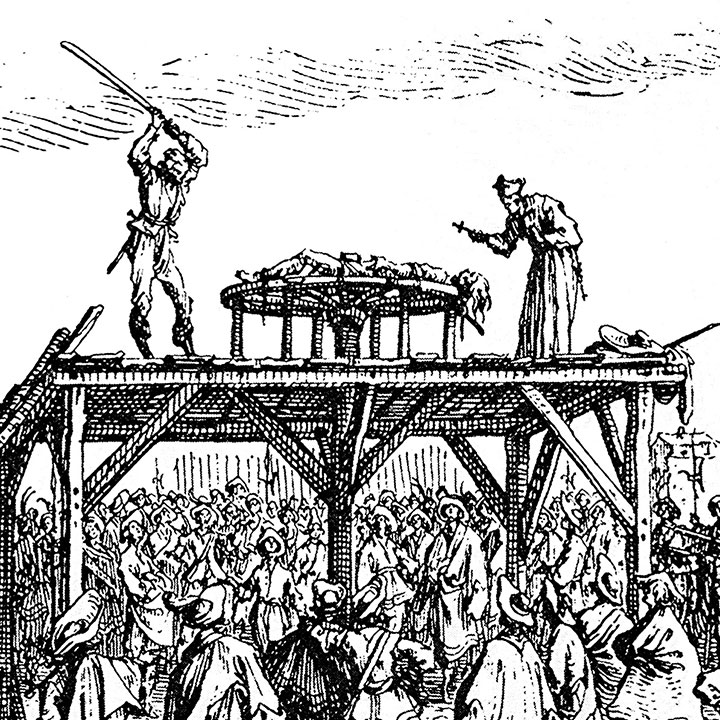

Historical records of public execution grounds in Berlin date back to the mid 16th century. The city’s first public execution ground was located near Ostbahnhof.

During Frederich III’s reign, the execution ground was moved to the area Mitte at the intersection of Oranienburger Straße and Krausnickstraße.

Located right in front of Monbijou Palace, the ground caused complaints from the ruler in the palace, which led to its swift removal and move to what was then Bergstraße, near the present-day Sophien cemetery.

Finally in 1753, the execution ground was moved one last time to Gartenplatz.

The last person to be publicly executed was Charlotte Sophie Henriette Meyer, commonly known as Widow Meyer, who murdered her husband by cutting his throat in his sleep.

At the time, convicts were executed by hanging, burning, and breaking wheel – a method using a large spoked wheel. Widow Meyer was said to be executed by breaking wheel. According to an urban legend, her ghost wanders around the execution ground in Gartenplatz to this day.

With the subsequent construction of St. Sebastian Church near Gartenplatz, the area no longer bears any resemblance to its former appearance. Lost and unable to find her own grave, the ghost of Widow Meyer wanders around this neighborhood every night.

A flashing light has been sighted coming from inside the church. Whether or not this was from a lit flame on an iron trivet is another matter entirely.

Gartenplatz, Berlin

Noh – Kana-wa (Iron Trivet)

A long time ago, there was a woman in Kyoto.

Embittered by her ex-husband for abandoning her for a younger woman, she became vengeful and walked a long distance to Kifune Shrine every night to curse him.

The Shinto priest gave the woman a divine oracle, which said that if she put an iron trivet lit with burning flames on her head and filled herself with rage, she would be able to turn into a demon.

As soon as the woman swore to follow the oracle, her appearance changed, and her hair stood on end as thunder rumbled.

Cursing her ex-husband to live and breathe through her bitterness, she disappeared into the thunderstorm.

Meanwhile, beset by nightmares every night, the ex-husband visited the renowned yin-yang diviner Abe no Seimei for help.

The diviner pronounced that the husband and his new wife would die from the curse of his ex-wife on this night.

Answering to the man’s pleading, Seimei set up an altar at the man’s house, onto which he placed the couple’s hat and wig. He then began to pray to transfer the couple’s curse onto the objects.

The ex-wife then appeared, transformed as a demon, and wearing a lit iron trivet on her head.

The demon lamented her grudge and attacked the hat and the wig but Seimei repelled her with his divine power. Swearing to seek another chance for revenge, the demon disappeared.

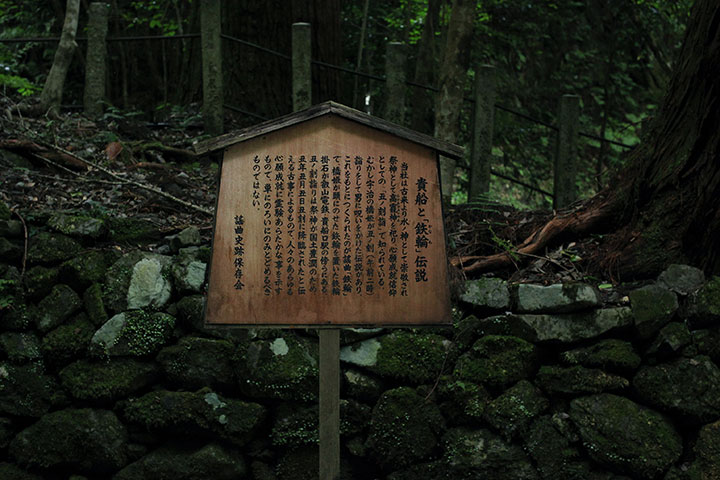

Kyoto – Kifune Shrine

In the Noh play Iron Trivet, a woman begrudging her husband for having abandoned her for a younger woman makes nightly visits to a shrine.

Nestled deep in the Kurama mountain of the northern fringe of Kyoto, the trek from the city center would have been arduous and treacherous – a testament to the sheer depth of her grudge.

Nowadays the shrine is well known as a place of good-luck for matchmaking.

Kifunecho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Kifune Shrine

Kyoto – Seimei Shrine

Abe no Seimei - the yin-yang diviner from Iron Trivet – is enshrined here.

Entrusted to cast out the pain and suffering of royalties, aristocrats and commoners, he was acclaimed as a diviner in all quarters. Built on the site of his former residence, the shrine is renowned for warding off evil spirits and misfortunes.

806 Horikwa-dori Ichio-agaru, Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto, Seimei Shrine

Kyoto – Kanawa no Ido (The Well of Iron Trivet)

The site is believed to be where the female protagonist of the Noh drama Iron Trivet resided.

According to one legend, this is where she ended her life by throwing herself into the well.

It’s also rumored that the iron trivet she wore is buried here in her commemoration.

In the past, the well was known as the well of severance, as making one’s lover drink its water was thought to end the relationship forever.

Kajiyacho, Shimogyo-ku, Kyoto, Kanawa-no-ido

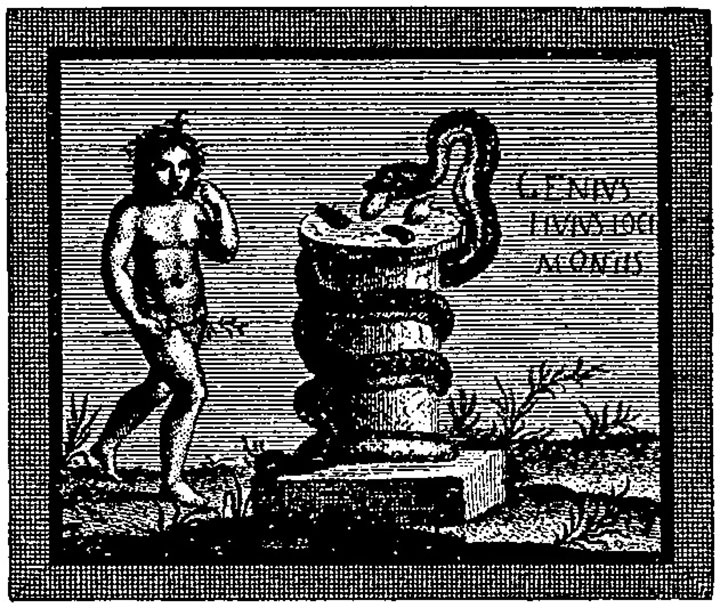

Genius loci

The Latin term genius loci originates from Roman mythology and is often translated as spirit of the place. The term tends to refer to a historically and socially accumulated sense of the place-ness.

In the poem Epistle to Burlington (1731), the phrase Consult the Genius of the Place is used prominently by poet Alexander Pope to advise his friend, and architecture and gardening enthusiast, Richard Boyle on landscaping.

Consult the Genius of the Place in all;

That tells the Waters or to rise, or fall,

Or helps th’ambitious Hill the heav’n to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the Vale,

Calls in the Country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks or now directs, th’ intending Lines;